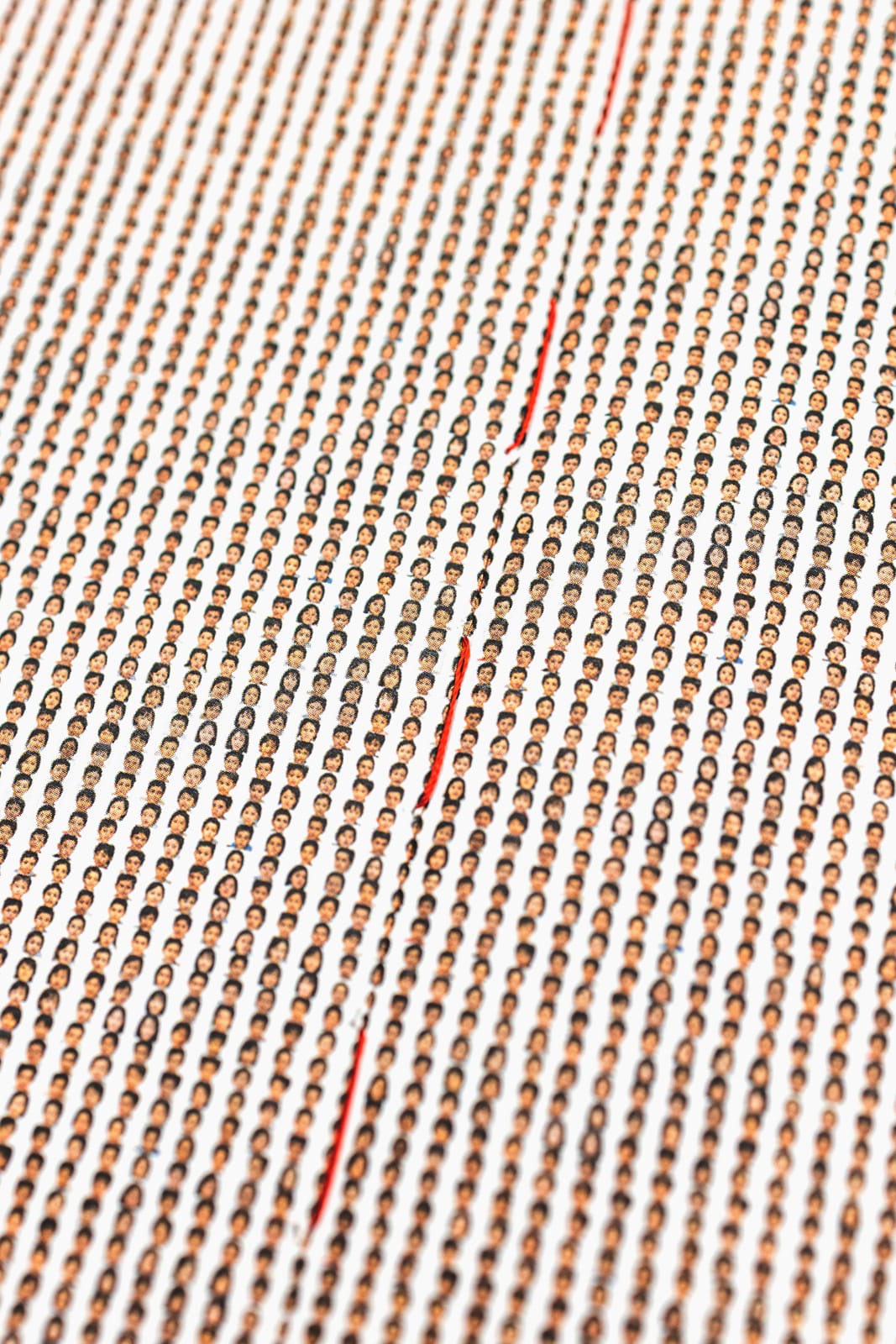

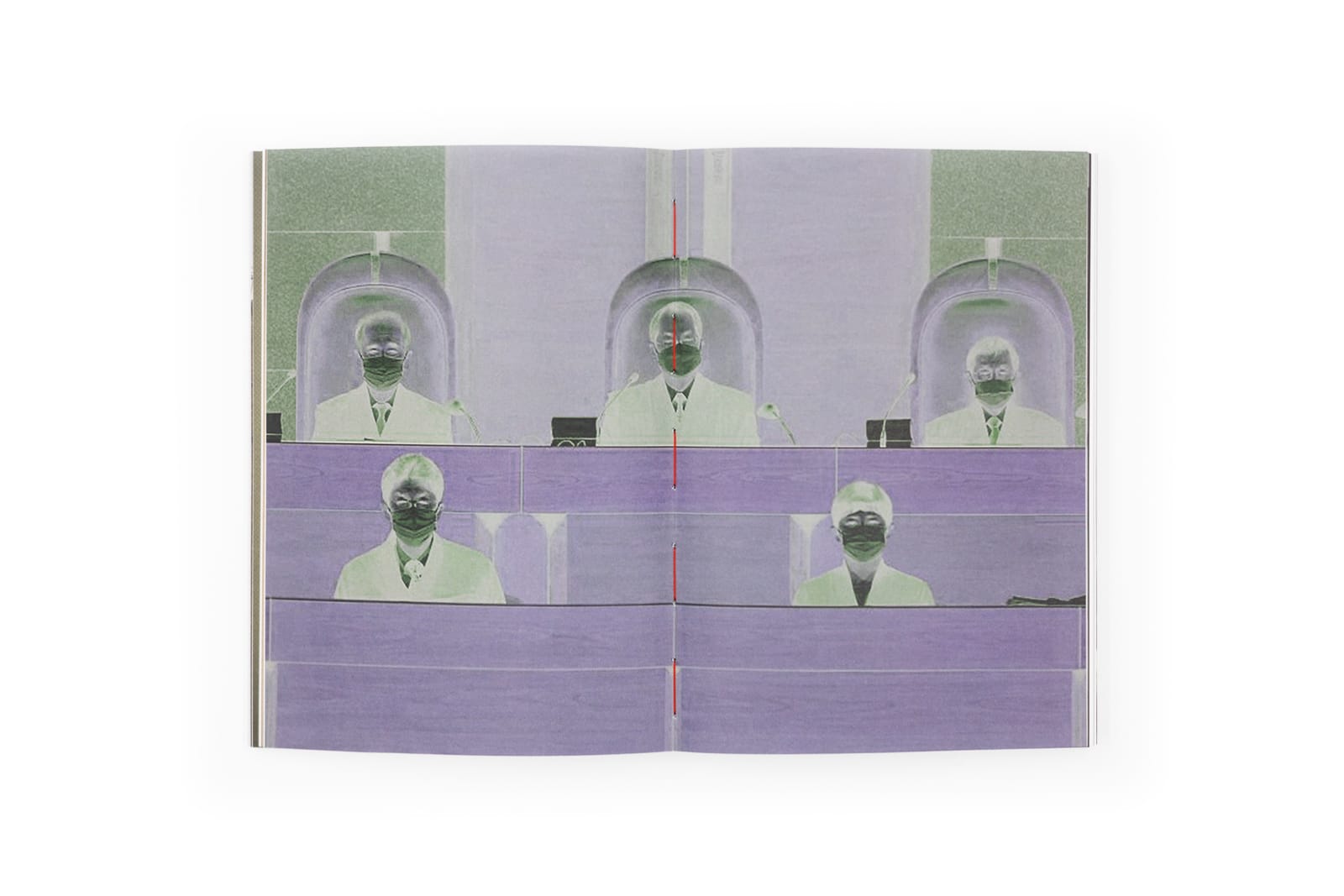

Japoński wymiar sprawiedliwości opiera się na XIX-wiecznych regułach funkcjonowania rodziny, które nie uznają podziału władzy rodzicielskiej i nie uważają uprowadzenia dziecka przez jedno z rodziców za przestępstwo. W rezultacie rocznie ponad 150 tysięcy dzieci traci kontakt z mamą lub tatą.

Japonia to jedyny kraj grupy G7, w którym po rozwodzie prawo do opieki nad dzieckiem przysługuje wyłącznie jednemu rodzicowi, drugi zaś zostaje pozbawiony praw rodzicielskich. Nie ma prawa wiedzieć, gdzie dziecko mieszka, gdzie się uczy, jak się czuje. Nie ma prawa do spotkań.

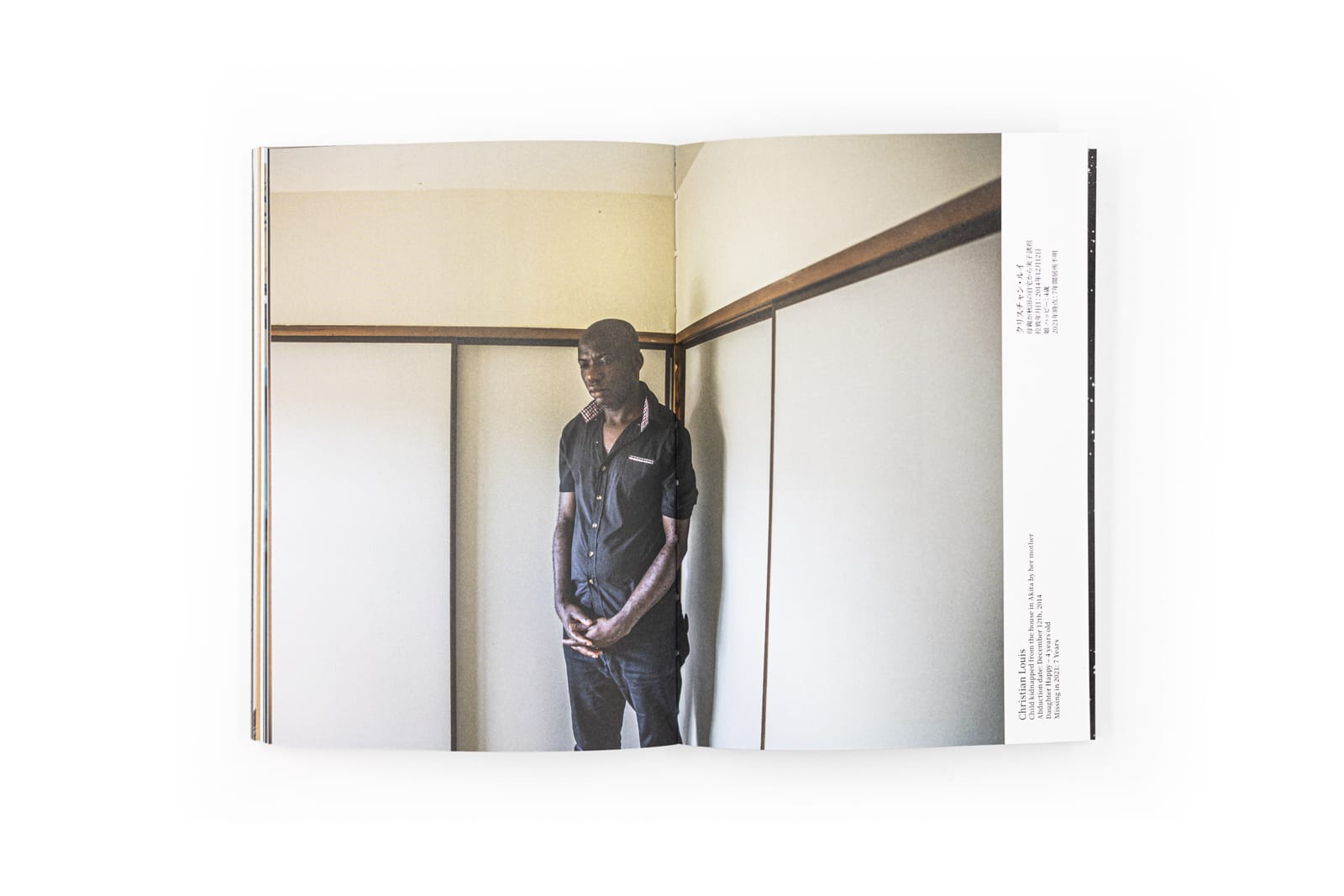

One day, you are a parent; the next, you are not. The police and the court say: *"Go home, forget that you were ever a parent! Imagine that your child is dead,"* recalls one of the people featured in the series.

But parents cannot forget. Tomas Savicas last saw his daughter, Gabriele, over eight years ago. He still catches himself looking into strollers on the street, searching for his nine-month-old daughter—the age Gabriele was when his ex-wife took her from their home.

*"Under the current Japanese law, the parent who manages to take the children first will be granted custody,"* explains Richard Delrieu, a professor at Kyoto Sangyo University and chairman of the SOS Parents Japan association, who himself lost custody of his son. *"The court tolerates child abduction,"* Delrieu adds in a documentary on Japan's family law. After six months of the child living in the new residence, the abducting parent gains a legal advantage over the other spouse. Custody is then granted to them.

It is often the case that a parent who has lost custody must—despite having no contact with their child—pay child support until the child turns 21. Between 10% and 30% of the child support payments go each month to the lawyers who helped secure the court ruling.

Anna Bedyńska

Her focus is always on people. She directs her camera toward those who live in the shadows of the wider world, often on the margins of social and economic life. She strives to capture the social changes shaping contemporary society, such as the evolving role of fathers or the situation of women in social, cultural, and political contexts.

Her projects Dad in Action, Clothes for Death, and Kids Go Home have been used as social campaigns advocating for the humanization of death and birth, while the Spot the Dot photo series was created to support skin cancer prevention efforts.

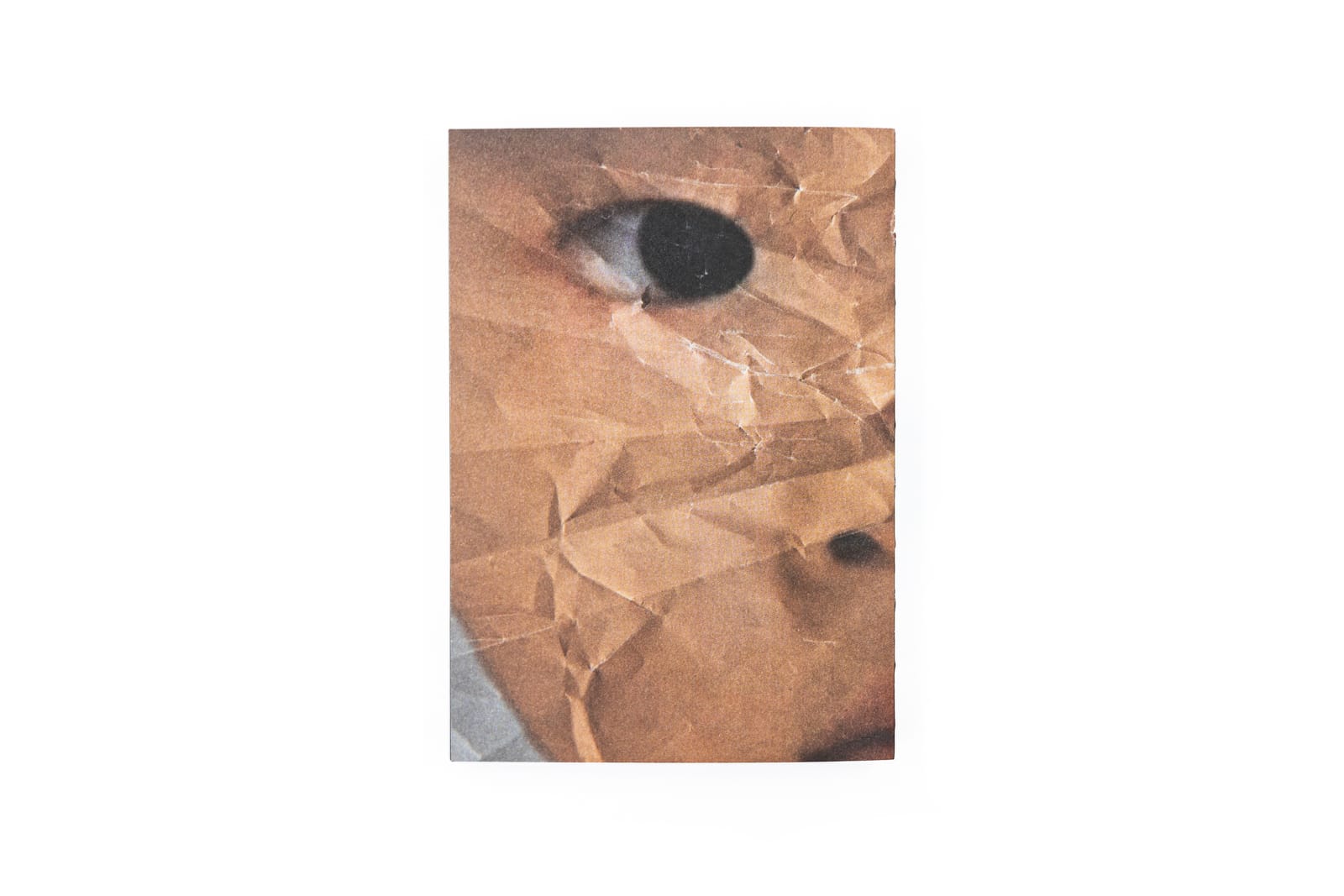

Anna Bedyńska specializes in reportage, often addressing taboo topics. In her project Forever Mine, she combines photography and sound to tell the story of parental abductions in Japan.

Laureatka nagrody World Press Photo oraz Nagrody MKiDN (2013). Ukończyła PWSFTviT w Łodzi oraz Szkołę Filmu i Teatru Dokumentalnego w Moskwie. Jej rosyjska seria „Niewinnie skazani” zdobyła tytuł Zdjęcia Roku w Grand Press Photo 2017. Członkini Canon Ambassador Program (2013–2018), Women Photographers i Polish Women Photographers. Mieszkała i pracowała w Warszawie, Moskwie, Tokio, Hongkongu i Bukareszcie.

www.annabedynska.pl

Makieta książki „Forever mine” (2021–2023) znalazło się wśród finalistów Hong Kong Dummy Award 2023 i w ramach tej nagrody książka podróżuje obecnie po festiwalach książek fotograficznych na całym świecie.